Together with physicist and data analyst Jarl Sidelmann I have just posted a bibliometrical study of hep-th on the arXiv. In this post I will explain what we did and what we have found.

In a new bibliometrical study we show that the levels of competition for survival in theoretical high-energy physics has increased dramatically during the past 40 years. We find evidence of a homogenisation of the research field where competition creates incentive structures that push young researchers into large communities while those who work alone are increasingly at risk of perishing. The result appears to be a risk-averse, conservative research community that has lost its creative powers.

A research community in crisis

There can be no doubt that theoretical high-energy physics (hep-th) is in a crisis. Since the discovery of the standard model of particle physics there has been no major breakthrough on the fundamental problems the field is facing — for instance the rigorous formulation of quantum field theory, the reconcilement of general relativity with quantum theory, and finding the origin of the standard model. At the same time the field has had very little empirical data to guide it forward.

In a situation where a research field has come up against a wall one would expect to see an explosion in new ideas and a diversification of the field with researchers taking off in very different directions searching for answers. And especially one would expect to see young researchers launch bold and daring research projects in new directions.

That is not what has happened in hep-th. Instead, the field has organised itself in a small number of very large research communities centred around a small set of quite old ideas — supersymmetry (1971), string theory (1974), loop quantum gravity (1986), the AdS/CFT correspondence (1997) to name a few — none of which have been able to produce any empirical evidence in their support; some of these have even been partly refuted experimentally (supersymmetry and string theory for instance). These research communities are surprisingly stable with very little movement between them.

This situation calls for an explanation. And since all this is clearly related to the culture and structural organisation of hep-th such an explanation must involve an analysis of the sociology of the community. It does not suffice to identify the problem and lament people for continuing to pursue and promote what many regard as failed ideas. Rather, we need to understand why those people have the positions they have and why researchers, who might have responded differently, do not. We need to understand why so many physicists choose to run in the same direction when the situation calls for the exact opposite, and we especially need to understand why young researchers choose to join one of the existing research communities instead of pursuing their own ideas. In other words, what we need is a deeper understanding of the underlying social dynamics of the community, what its social forces are, and how these forces have changed over time.

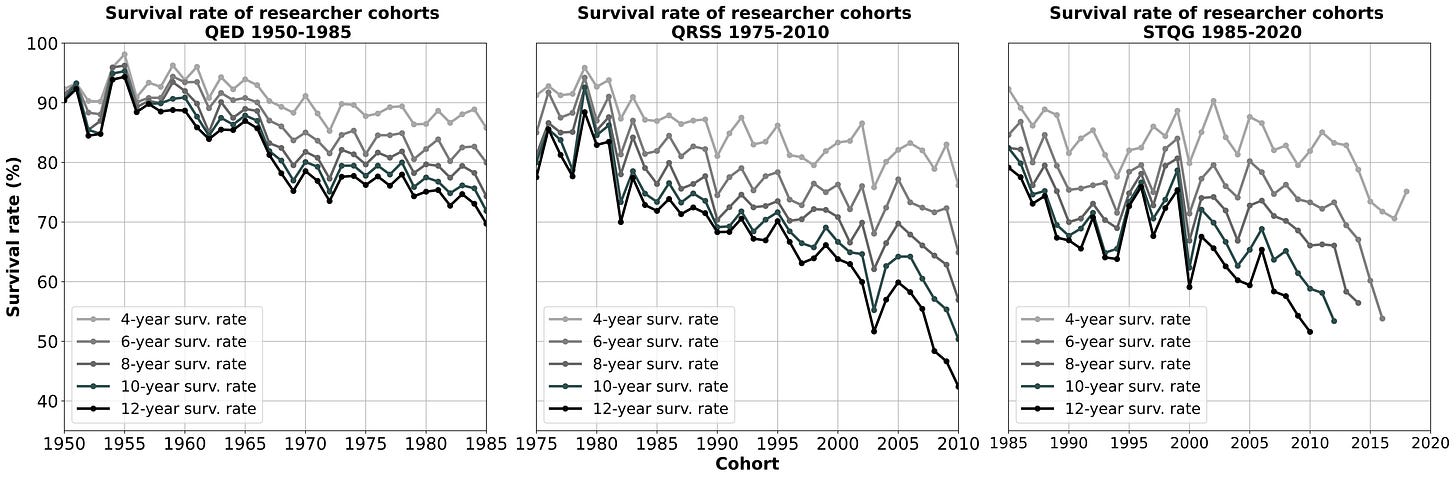

Survival rates after 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 years in academia based in three samples between 1950 and 2020. These rates are conservative estimates; the true survival rates are almost certainly lower.

The homogenisation of hep-th

About a year ago I teamed up with the theoretical physicist and data analyst Jarl Sidelmann to analyse publicly available publication metadata from hep-th. Our aim was to chart the historic developments of the incentive structures in the community and through that gain insight into its social dynamics.

Concretely, we charted the levels of competition in the community between 1950 and 2020 and analysed correlations between survivability and various bibliometric measures such as rates of collaboration, production, and received citations.

- the levels of competition for survival have increased dramatically over the past 40-50 years. In 1950 there was essentially no competition, almost everyone who published a couple of papers in the field went on to have a full career. The level of competition began to increase around 1980 and today the competition is fierce with survival rates below 50%1 and a duration of competition that is essentially open-ended.

- both surviving and non-surviving researchers have increased their levels of production and collaboration during the time-span of the study. However, surviving researchers have increased their levels of collaboration considerably more.

- survivability of young researchers can be modelled by a two-variable regression model with moderate success in the years after the mid 1990s. This is not possible prior to the 1990s.

What does this tell us?

First of all, it tells us that the community of hep-th is in rapid and ongoing transformation. The levels of competition is rapidly increasing and the community is changing accordingly. From a sociological perspective hep-th today is a completely different entity compared to just 30 or 40 years ago.

Secondly, it is clear that when the level of competition increases dramatically in a scientific community then young researchers, who are at risk of expulsion, will begin to behave differently. Competition creates selection pressures and incentive structures that necessarily impacts the entire community.

A key factor in understanding how increased levels of competition translate into incentive structures is the metric used to evaluate researchers and their research. During the past decades there has been a shift away from peer-review and towards measuring and ranking academics through quantifiable proxies such as production and citation numbers. It is therefore reasonable to expect young researchers to begin competing on these parameters, which is partly confirmed by our observations.

Indeed, our results indicate that the main effect of the increase in competition is to force young researchers to collaborate more. There are several reasons why collaboration is a successful survival strategy:

- Collaboration is an easy way to boost production numbers. If two researchers team up their individual production numbers will double2.

- Collaboration can expand ones social network. Working with influential researchers can be a career booster, provide access to funding, and increase one’s chances of being cited.

- Collaboration is rewarded by funding agencies.

Our analysis clearly shows that collaboration is an effective survival strategy. Young researchers in hep-th, who work alone, are in serious peril.

Now, there may of course also be more benign reasons why young researchers choose to collaborate more. For instance, teaming up with researchers with different skillsets may be a more effective way to solve complicated problems. However, the point is that it does not matter what motivates people to collaborate more. What matters is that an increase in the level of competition creates a selection pressure that favours some and disfavours others, and the question is whether the change that this brings about is for the better?

That the community has changed is clear. The fact that survivability after the mid 1990s can be modelled with a simple two-factor regression model based on science proxies, something that is not possible prior to the mid 1990s, indicates that the community is transforming in a fundamental manner. It should be impossible to model a scientific community in such a primitive fashion, the fact that it can be done is truly surprising. Note that the period where the modelling begins to be effective coincides with the period where the level of competition begins to grow. This indicates that competition changes the behaviour of researchers and that the community as a whole is adapting by becoming more homogenised.

Mainstream as a survival strategy

What is the effect of all this?

When incentive structures reward young researchers for collaborating more and punishes them for going solo, then a social force is created that pushes the field towards mainstream research. This means that being a member of large research communities is an effective survival strategy. In a community it is easier to find collaborators that will help you drive up your production numbers and it is easier to create a network that will help you promote your career. In contrast, if you work on your own ideas far away from mainstream research you will be less likely to find collaborators, you will have less access to influential researchers and their networks, and your chances of being cited go down.

This also means is that there will be an incentive for young researchers to avoid controversial research topics and instead work on topics that are popular. But that must mean that the field will be pushed in a more risk-averse, standardised, norm-preserving direction. A direction where the emergence of conceptually new ideas, which almost always emerge at the bottom of the social hierarchy, is being hindered.

— which sounds a lot like what is going on in hep-th today. A lot of ‘more-of-the-same’ and very little radically new ideas proposed by people at the bottom of the hierarchy.

1920 vs 2020

The community of hep-th is today in a situation that in many ways resembles the situation that it was in at the beginning of the 20th century. Back then the field stood at the brink of discovering quantum mechanics and general relativity, it was a period where it was completely unclear in what direction the field should move forward. When we look at the physicists who made the key breakthroughs back then three things stand out:

- they were very young when they did their most important work. Typically around 30 years or younger.

- they worked alone.

- they worked in very different directions.

For instance, Niels Bohr was 25 years old when he published his atomic model in 1911. Albert Einstein was 26 years old when he published his famous four papers in 1905. Paul A.M. Dirac was 26 years old when he published the equation that is today known as the Dirac equation. Werner Heisenberg was 26 years old when he published the uncertainty principle. All these legends worked alone, as did almost all of their contemporaries, and many of them worked in very different directions. Compare this to today where young researchers are not young anymore when they are finally free to work on their own projects. Our data shows that researchers in the 21st century keep competing for survival for more than 10 years after having entered the field.

It seems clear that the increased levels of competition go a long way in explaining why the field anno 1920 reacted so very differently to a situation that in many ways is similar to where we stand today. Competition for survival does not enhance quality, rather it drives researchers towards herd mentality and group think and pushes out those who dissent. In other words, the community is becoming more of a monoculture. The odd types, the outliers, are being weeded out while the conformists take over.

Where are the sociologists?

This project began as a search for literature. During the past years I have become increasingly interested in the sociology of contemporary academia, especially hep-th, and at some point I started to search the literature for studies that could help me understand what I saw as a dysfunctional scientific community. I often discussed this with Jarl, who is a good friend of mine, and together we started to dig ourselves into the subject. We were convinced that competition is a central factor — anyone in science knows that the fight for survival is one of the top priorities of any young researcher in contemporary academia. So we searched for studies that charted the historic levels of competition.

We expected that the literature on the topic would be extensive but to our surprise we did not find much. In fact, we found only one paper that attempted to map the levels of competition in the period 1960-2010, but that paper had some sources of error3 that made us question the validity of its results. Apart from that there was nothing.

We read a lot of literature on the subject but found that the word “competition” was strangely absent everywhere. For instance, in the book “The science of science” written by Dashun Wang and Albert-László Barabási, which is a review of the research field that studies science — a mix of sociology, bibliometrics, scientometrics, data-analysis, etc — competition for survival is not mentioned as an important sociological factor at all. Similarly, the paper “A century of physics” authored by Roberta Sinatra et al, which is a bibliometric study of physics spanning 100 years and involving millions of papers, claims to unveil ”the anatomy of the discipline” but does not mention competition for survival at all.

As our work progressed this became a major puzzle. Surely the sociologists studying science must have monitored and analysed the levels of competition in the field, so where were all the studies? At some point we contacted 25 leading researchers in the sociology of science and asked them. Only one replied. A prize-winning sociologist with almost 600 publications on the sociology of science told us in a short email that there are “many empirical analyses available“ but when pressed for specifics he admitted that he did not know the literature well enough to answer our question.

This makes no sense. Is it really possible that the sociologists studying science have missed what is obviously one of the most important sociological factors in science? That would be a stunning omission. It would be as if physicists had forgotten to include gravity in their description of the physical reality. Nevertheless, the answer appears to be yes.

Now, some readers might wonder why this is such a big deal. After all, who cares if the sociologists have missed something important? This is a mistake for two reasons:

First of all, just as it is the climatologists job to warn us about increased levels of carbon dioxide and inform us about the consequences of our greenhouse emissions, so it is the sociologists job to warn us about the negative consequences that rapidly increasing levels of competition might have on science. If the sociologists are not doing their job then we are in a sense flying blind.

But even more importantly, the sociologists and people involved in ‘science-of-science’ often have very close connections to policy makers and thus they have direct influence on the way the scientific community is being administered and shaped. And it seems clear that at least some sociologist have some very dangerous and misguided views on science. Here are a couple of quotes from influential researchers in the field:

“The science of science (SciSci) places the practice of science itself under the microscope, leading to a quantitative understanding of the genesis of scientific discovery, creativity, and practice and developing tools and policies aimed at accelerating scientific progress.”4

and

“… such quantitative understanding could help us identify as yet unexplored research areas.A better understanding of the optimal paths of innovation may also change the way we fund scientists and institutions to unlock their creative potential and enhance their long-term impact.“5

and

“By analyzing large-scale data on the prevailing production and reward systems in science, and identifying universal and domain-specific patterns, science of science not only offers novel insights into the nature of our discipline, it also has the potential to meaningfully improve our work. With a deeper understanding of the precursors of impactful science, it will be possible to develop systems and policies that more reliably improve the odds of success for each scientist and science investment, thus enhancing the prospects of science as a whole.”6

The idea that quantitative methods can be used to optimise, accelerate, and guide science is fundamentally misguided and dangerous. To understand precisely why that is the case we need to turn to economics, where the British professor Charles Goodhart has pointed out a key characteristics of measures.

Goodhart’s law

At the core of this discussion is the idea that quality of research can be measured using quantifiable metrics. That is, that the researchers who produce the most, have the most impressive CV, are cited the most, etc. are also the “best” researchers. However, the economists have long understood that such an idea comes with a serious risk of a back-reaction. In particular, the so-called Goodhart’s law states that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure“.

In other words, it may at some point be possible to measure quality quantitatively, but once you begin rewarding researchers based on such measures they will unavoidably begin to compete on these measures, which as a result will deteriorate as measures of quality. It is quite obvious and we see signs in our analysis that this is already happening in hep-th.

This is the reason why the efforts of some sociologists of science is so dangerous. These sociologists clearly do not see the danger posed by the back-reaction described by Goodhart’s law — in fact, it is remarkable that Goodhart’s law is not being widely discussed among sociologists of science7 — namely that by using quantifiable measures of quality you risk transforming science into an industry whose main purpose is to optimise those very measures. Gone is the pursuit of truth and enlightenment, the new goal will be to increase production, impact, and citation numbers.

What comes next

The study that we have just made public is intended as a foundation for further studies. It is clear that this topic requires more attention and further analysis. We hope that others will pick up the baton and join us in our efforts to understand what is going on in hep-th and in academia in general.

I would also like to emphasise that it is Jarl Sidelmann who carried out all the data analysis that we have published and thus he deserves all the credit.

With this I will end this newsletter. As always I would like to thank all of my sponsors, who has made this work possible.

Take good care everyone,

Best wishes, Jesper

________________________________________

Footnotes:

1 For technical reasons we are only able to provide upper bounds on survival rates. That is, the actual survival rates are almost certainly lower than what we have been able to determine.

2 If a group of N researchers, who otherwise work alone, were to simply to add each others names as coauthors to all papers published in the group, then the individual production numbers for all members of the group would go up by a factor of N. The point is that the incentive structures reward individual production numbers and collaborations, and thus there is a double incentive for researchers to team up regardless of what scientific merits such a collaboration might have.

3 To be specific, the paper uses a sampling technique that involves a very obvious and serious source of error. Also, it does not employ any segmentation, which means that it throws researchers with very different circumstances into the same samples.

4 Santo Fortunato et al. Science of science. Science 359, eaao0185 (2018).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aao0185

5 Sinatra, R., Deville, P., Szell, M. et al. A century of physics. Nature Phys 11, 791–796 (2015).

https://www.nature.com/articles/nphys3494

6 The Science of Science by Dashun Wang and Albert-László Barabási. Cambridge University Press (2021).

7 For example, in the book The Science of Science the authors ask the question “are better cited papers really better?” only once (section 3.2.3), and answer it in the affirmative by citing references that are between 46 and 26 years old. I contacted the authors and asked them why they do not consider Goodhart’s law and why they do not cite more recent studies. I never heard back from them.